|

Choice of material

was never a problem. "Mostly (we did) songs that we liked to do, and that people enjoyed," Clay says. "Of course, pacing was

important. We'd be on stage for an hour and a half." The highlight of The Surfers' stage act were Dean Martin/Jerry Lewis-styled

comedy routines that the Naluai brothers worked up nightly. "I was the straight man, and my brother was the comic. What happened

between my brother and me, we never planned. Nobody sat down with us and said, 'do this, do that.' If it was funny (for the

audience), we just kept doing it over and over again. It just evolved as we were performing on stage." Clay reveals that the

clown role didn't come naturally to Alan. "Many comics are not funny when they're not working, and he was one of those types

that wasn't. But on stage, Alan was hilarious! I couldn't look at him! He would do things spontaneously, and I would just

be cracking up!" Reviewers raved about Alan's comedy turns, and also applauded what they came to describe as "Clayton's romantic,

leading man posture." But the mainstay of Surfers shows was always their singing. Modest Clayton Naluai may be, but he isn't

at all shy about expressing pride in the sound his group achieved. "Our harmony was great! We worked at it. We couldn't just

get up on stage and sing. We had to be aware. We had to listen to one another. (When) we practiced singing, we'd go into a

hall, and each one of us would stand in a corner . . . and we would sing a song. But we wouldn't sing it in parts. We'd all

sing the melody! The goal was to have it sound like it was all coming from one voice." It was the same sound that made their

recordings so special. "When the voices are like one, " Clay believes, "there's a 'ring' to it. Many times

we hit it, and sometimes we didn't . . . but we were always going for the 'ring.' Audiences who heard them hit 'the ring'

were delighted to discover that no studio trickery had been used to enhance The Surfers's natural singing abilities.

The

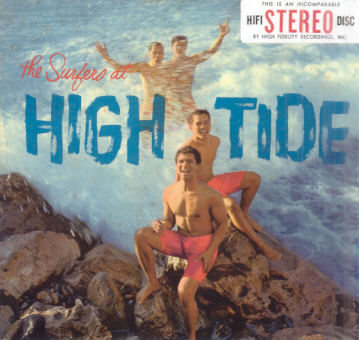

boys may have been learning the ropes on stage in 1959, but they could do no wrong in the studio that year. They released

a pair of albums that rank as the finest in their HiFi catalog: The Surfers At High Tide and Tahiti. On

the former, the group delivers romance with a capital "R," wrapping their golden voices around a rare all-English language

collection (with some of their trademark chanting sprinkled in, naturally). With Al often taking the lead, the boys display

their tightest harmonies yet. Accompanying them is a small orchestra conducted by Hall Daniels, whose warm and colorful arrangements

drape themselves like palm fronds over the album's twelve selections. Female fans were no doubt delighted to hear this sparkling

set of picturesque standards. "Red Sails In The Sunset," "Beyond The Reef," "Canadian Sunset" and "Return To Paradise" hold

forth alongside Latin favorites like "The Breeze And I" and "Perfidia." With its tropical sound effects, "Jungle Drums" sounds

like it could've come from the same recording session that produced Martin Denny's smash hit "Quiet Village," also from '59.

The album's standout track is "Legend Of The Rain," a dramatic story song. The Surfers' choral narrative is punctuated by

crashing cymbals, trilling harps and a thundering kettledrum. Performed in its entirety with the right kind of staging, this

album would've made one hell of a musical revue.

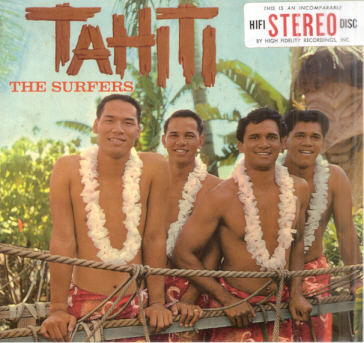

If

sailing At High Tide delighted women, they were surely beside themselves with joy when The Surfers then invited them

to embark on an adventure to Tahiti . . . especially once they saw how little in the way of clothing the boys wore

on the album sleeve! Is this really a studio album, or could it be the lost soundtrack of a 1930s South Sea island melodrama?

Eddie Bush's curling steel guitar snakes in and out of swaying ukelele melodies one minute, and weaves through staccato rhythm

sketches the next. The latter come courtesy of Bob Nichols' insistent tom toms, which beat a fiery tattoo into the imagination

and conjure up images of ancient tribal ceremonies. Taboo! Grass skirts are swishing furiously as the "Drums Of Tahiti" sound

in the distance. The boys pour lots of bravado into this number; in fact, their full-bodied singing raises the testosterone

level so high, you half expect the stuff to come spurting out of your speakers! Male singing voices never sounded more virile

than The Surfers' voices do on "Beauty Hula," which climaxes in a series of layered shouts that tumble one after another domino-style.

This is definitely one of the boys' most exciting and elaborate chants. Their spirited vocal riffing here and on "Ulili E"

and "Kau Kino Mambo" is guaranteed to revive even the most listless of luaus! Robust Polynesian chanting abounds on this LP,

but it wouldn't be a Surfers album without ballads. Tahiti contains some of the group's best. Like a sundown spreads

shimmering colors over the evening surf, the boys spread their exquisite vocal blend over languorous love songs like "Kuu

Lei," "Love Song Of Kalua" and the unforgettably tender "My Sweet Sweet." Then, Al and Clay share a jaunty lead on "My Wahine

And Me," an unexpected but welcome detour into jazzier territory. The "South Sea Island Magic" that the group sings of so

earnestly can be found in abundance within these grooves. The Surfers' final HiFi album was 1960's The Islands Call. Sounding

like a collection of out takes from their previous LPs, it breaks no new ground. Even so, the boys' swinging renditions of

"Sophisticated Hula" and "Keep Your Eyes On The Hands," as well as their stunning version of the wanderlust ballad "Faraway

Places" make it an album well worth having.

During the

twenty-plus years of the group's existence, The Surfers worked with many well-known entertainers, but without a doubt, their

most famous collaborator was Elvis Presley. The opportunity to work with him came through the intervention of executives at

Decca Records; Decca signed them after their HiFi Records contract ran out (and for some unknown reason, temporarily changed

their name to "The Hawaiian Surfers"). The label's parent company was MCA Corporation, which also controlled Paramount Studios,

and Paramount was the company that produced Blue Hawaii, Elvis's eighth movie. "On the (soundtrack) recording, they wanted

to have an (authentic) Hawaiian sound," Clay recalls. "So they asked us if we'd be willing to do the soundtrack album with

him." Were The Surfers up for cutting a record with the King of Rock 'n' Roll? You bet your wahini they were! On March 21,

1961, Al, Clay, Bernie and Pat made the scene at Radio Recorders in Hollywood, where they met Elvis, his regular backing vocal

group The Jordanaires, and musicians including guitarist Scotty Moore, steel guitarist Alvino Rey, drummer DJ Fontana, pianist

Floyd Cramer and sax player Boots Randolph. Under the supervision of Paramount music director Joseph Lilley, they worked on

both original songs and traditional material like "Blue Hawaii," "Aloha Oe" and "The Hawaiian Wedding Song."

"We

spent three days in the studio. . . that's how long we spent working on that soundtrack. We had a great time doing it! (Elvis)

was a nice, nice guy. He wasn't a prima donna." Immediately after the sessions were over, Elvis returned to Hawaii for location

filming. With their muscular, tanned bodies and photogenic faces, The Surfers would've made ideal movie extras, but unfortunately,

they weren't asked to appear in the film. However, their trademark sound enhanced both the film's production numbers and the

blockbuster soundtrack album. It shot to number one around the world, holding the top position for 20 weeks in the United

States alone! In fact, Blue Hawaii stayed on Billboard's Album Chart longer than any other Elvis album. As if that weren't

impressive enough, the single from the sessions earned a Gold Record almost instantly. "Can't Help Falling In Love With You"

b/w "Rock-A-Hula, Baby" was a double-sided smash that went on to become a fixture on oldies radio. The Surfers' satin-smooth

harmonies embellish both sides; Alan Naluai's frenzied chanting of rock! rock-a-hula! kicks off the latter, and provides

the record's strongest hook. Ironically, as much fun as he had working with Elvis, Clayton Naluai's sharpest memory of him

is how sad his life seemed. "He couldn't just go do what he wanted to do," Clay observed. "If he walked anywhere, he'd be

mobbed! He had this entourage of guys that went around with him, just to keep him company. Otherwise, he'd have been a very,

very lonely man."

Years

later, the brothers Naluai did get the chance to appear on screen, supplementing their music careers with small roles on TV

and in motion pictures. "'Hawaiian Eye' was the first TV show I appeared on, with Jack Conrad," Clay says. "And then I did

some of 'Hawaii 5-0' with Jack Lord. My brother did more of that than I did. (Alan) was in the movies! He was in the movie

Hawaii, and also The Hawaiians which was the follow-up. He was in about three or four movies. He did a lot of television,

too . . . 'Magnum PI' and other shows." Had it been up to Clay, though, he would have left all the acting to his brother.

"That's one part of entertaining that I really didn't enjoy. You may get an early call, or a late call, whatever, and when

you get there, you can be sitting around for six hours before you get to shoot anything! If I could just go in and do it,

and get out of there, that was fine with me!" His real passion was molding The Surfers’

stage act, and then giving his all in performance night after night. During his years as a performer, he studied aikido under

Japanese sensei Koichi Tohei, and believes that the discipline he took from martial arts training helped him become a better

musician. "The essence of who I am manifested itself (on stage)," Clay explains. "Because of that, I was more in touch with

the other person's spirit, the essence of who they are. You forget yourself, and all your focus is on (the group). It's the

concept of serving . . . my teacher called it 'toku,' serving without seeking attention or reward."

Throughout

the 1960s, The Surfers served as ambassadors of Hawaiian music to mainland audiences. They regularly played upscale nightclubs

in Hollywood and Las Vegas, such as the fabled Flamingo and Stardust clubs, and toured as far east as Chicago. However, during

those years, Hawaii was just another touring destination for them. "Our base was in California," Clay says. "It was a lot

easier to travel from California than it was to travel from Hawaii six or eight or nine months of the year. Our families,

our wives and children, were all in California, and we would commute from our homes to wherever." Married life took drummer

Bernie Ching out the group shortly after they recorded an album of motion-picture themes for Warner Brothers Records. At his

wife's request, Bernie quit to spend more time at home. He was replaced by Joe Stevens, another native Hawaiian musician despite

his English surname. By 1969, all of the boys were tired of touring, and ready to move back home. Yet according to Clay, their

return was fraught with anxiety. "When we first came back to Hawaii as a group, in 1969, we weren't sure if we were gonna

be accepted! There were no "acts" (like us) in Hawaii . . . we started in California, and so we were unique. I guess we were

accepted because we were so different." Their years on the mainland had given The Surfers a degree of professionalism that

was new in Hawaiian music circles. They added Hollywood gloss and polish with what Clay liked to call "a Hawaiian spirit."

The combination proved to be a potent one, and The Surfers were welcomed at the islands' top venues: Don The Beachcomber's,

The Outrigger Waikiki, The Club C'Est Si Bon and the Imperial Hawaii Hotel, just to name a few. Buddy Naluai joined the group

during this period. "He was just kinda hanging around in Waikiki," Clay recalls. I said, 'Hey Buddy! Come work with us.'"

With brother Buddy on board, it was more of a family affair than ever, and for another decade, The Surfers sang and played

and plied their unique brand of entertainment. They also continued to record albums for independent labels, winning critical

acclaim with a 1974 collection called Shells. When the ride finally ended for the group, family concerns were once

again the catalyst.

In January of 1980,

the Naluai family patriarch was diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease. It was devastating news for the entire family, but Clayton

Naluai was affected in a very profound way. "I was 43 years of age at that time. I thought, my father could've retired when

he was 43 . . . he could've had at least 20 years of retirement!" Of course, Alzheimer's can be hereditary, and this fact

obviously weighed heavily on his mind. Time became precious for Clay, and he decided that however much he had left would be

better spent with his wife and children. "On January 16, 1980, I said to my brother Al, 'I'm stopping,'" he reveals. "And

so I just stopped, and that's why the group broke up. When we broke up, Joe (Stevens) went and did things on his own, and

my brother went and did things on his own." Pat Sylva soon founded his own group, and Clay settled into an early retirement.

However, The Surfers had one more wave to ride.

One day,

Clay and his wife Margaret ran into Hawaiian superstar Don Ho in the parking lot of a Honolulu movie theater. Unaware that

The Surfers had broken up, Ho expressed interest in having the group open his new stage show for him. Clay explained that

the group no longer existed, and when Ho suggested a reunion, he stated unequivocally that he "didn't want to be up at two

or three o'clock in the morning, working!" But the Hawaiian music superstar was not easily dissuaded. He eventually talked

Al and Clay into an opening act, but only on Clay’s terms. It

had to last no longer than fifteen minutes! "I'd leave home about a quarter to eight, get there, park my car, walk backstage,

and change my clothes just in time for the announcer to say ladies and gentlemen! The Surfers!" Clay chuckles. "And then we'd walk out, just Clay and Al. We'd perform, and fifteen minutes later, I'd go

back, change my clothes again, and I'm home! That was fine with me. At that time, (Don Ho) was appearing at Duke Kahanamoku's

club, in the International Marketplace. Then he went over to the Hilton Hawaiian Village Dome." As popular as ever with audiences,

Al and Clay remained part of the Don Ho Show until the Hawaiian Village Dome closed, and then Clay promptly went back into

retirement. On rare occasions, though, the two-man edition of The Surfers would reunite . . . for instance, to entertain aboard

the cruise ship Independence in the year 2000, or to record duets like "You Gotta Feel Aloha," which became a local hit.

Al was

recording an album and preparing to launch a solo career when tragedy struck. "One day, he asked me to bring him something,"

Clay remembers, "and I went to take it to him. I noticed he was very . . . he looked very drawn. He was still performing and

recording. I actually said to him, you need to stop . . . you're killing yourself. Stop! (But) he didn't." On March 10, 2001,

heart disease claimed Alan Naluai at age 62. Although he'd suffered an earlier heart attack, his death came as a complete

shock to his family and friends. His funeral was held at Kawaiaha'o Church in Honolulu. "He was a very likeable person," Clay

says, "but I'm prejudiced about that." The three thousand mourners who crowded the church on March 18 proved that Al's likeability

was much more than a matter of prejudice. Music from his solo CD, which was issued posthumously, was performed at the memorial

service. He was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in the ocean off Waikiki . . . an appropriate burial for a man who

became famous as a Surfer. In March 2005, the surviving members of The Surfers (including Bernie Ching) reunited in Honolulu

for a one-off benefit performance for the American Heart Association. Stepping to the microphone, Joe Stevens told the capacity

crowd at Kapono’s Lounge that the group’s performance that

night was in honor of Alan’s memory.

Today,

forty-six years after his first Aikido lesson from Sensei Tohei, Clayton Naluai is himself a sixth dan Aikido sensei who runs

his own school of instruction in Honolulu. He has a daughter who performs as a dancer, and a nephew, Alan Naluai, Jr, who

carries on the family's musical tradition as an entertainer in Sweden. Clay looks back fondly on his years as an entertainer

and (though he’s loath to admit it) an Asian-American sex symbol!

"I enjoy entertaining now," he admits, "only I don't do it regularly anymore." With his rich, masculine speaking voice, burning

bedroom eyes, and wavy white hair, it’s a sure bet that this silver fox can still get the cocoanut milk flowing when

ladies are around! The Surfers, along with their contemporaries Don Ho and Alfred Apaka, brought a higher standard of musicianship

to Hawaiian entertainment. Yet if you ask Clay what the most important element in the group's success was, he’d say it was their ability to have fun together.

"Our act evolved from just singing to singing and having fun! (It's) all right to get up on stage and enjoy yourself. That's

why we were together for so long." Fun, sex appeal, Hollywood flavor and Hawaiian spirit. There you have it in a (cocoa)nut

shell . . . the story of The Surfers.

Special thanks

to Clayton Naluai.

|