|

"When people thought of Hawaiian

music," remembers Clayton Naluai, "they always thought of hula girls." Seductive Polynesian beauties, naked or nearly so,

swishing grass skirts back and forth . . . sending out, to the mainlander's eye at least, a wanton invitation. Suburban men

in the 1950s would put Hawaiian music albums on the hi-fi set and fantasize about the brown-skinned beauties pictured on the

LP sleeves. To paraphrase the popular novelty song "Keep Your Eyes On The Hands," he'd want to "mow the grass" . . . much

to the consternation of his wife, to whom the subject of his fantasies was only too obvious. Hmmph! Ah, but she could take

her sweet revenge a little later. She could play her Surfers albums! The Surfers definitely weren't hula girls. They were

tanned, brawny and buff Hawaiian men, appealingly young and exceedingly virile. More likely as not pictured shirtless on their

album sleeves, The Surfers looked like the kind of men who'd sweep a woman off her feet and whisk her away to an exotic island

. . . an adventure that promised of all manner of naughty, sweaty fun. Who needs a grass skirt when the cocoanut milk is so

sweet? With their muscular appearance and a vocal style that could be either just as muscular or softer than satin, The Surfers

were an act tailor-made for wooing women record buyers . . . as well as the occasional male Hawaiian music enthusiast, so

long as he wasn't threatened by their bare-chested masculine appeal.

Although the

group was almost entirely the creation of a West Coast record company, the talent that fueled it wasn't manufactured. It was

born and bred in Hawaii, and it centered around the singing brothers Naluai. "We come from a very musical family," Clayton

Naluai confirms. "My brothers and sisters always studied music. We were six children, and I am the oldest. Alan was the second

youngest child." Clayton says he didn't devote himself to musical studies as vigorously as the others did, modestly referring

to himself as "the least talented musically of all the siblings." Yet, his strong lead voice, alternating between tenor and

baritone, appears on many Surfers records, and he was without question the driving force behind the group. Clayton Naluai

could also strum a mean stand-up bass. For his part, Alan Naluai played guitar - an instrument he'd studied from a very early

age - and sang in a sweet, pure tenor that belied his brawny frame. Youngest brother Buddy Naluai also sang; he would eventually

join The Surfers, too, but not until after the original quartet had made a name for itself.

In 1957, Al

and Clay were attending Glendale Junior College in Glendale, California. There they befriended two other native Hawaiians:

percussionist Bernie Ching and Pat Sylva, a multi-instrumentalist who could hold his own on piano, vibes, ukelele or trombone.

Both Pat and Bernie sang as well. They all ended up joining the school choir, and traveling up and down the West Coast doing

concerts. One day, the choir director asked the four friends to work up arrangements of some traditional Hawaiian tunes and

perform them as specialty numbers. They did, and the boys' act went over big on stage. That's when, according to Clayton,

"we started having fun with it." Tropical island kitsch was a major suburban fad in the years following World War II, particularly

anything that evoked Hawaii. North Americans' taste for Hawaiian music had been growing ever since Ray Kenney's band kicked

off a hula craze in the 1920s. Now that the Hawaiian islands were poised to become the 50th state, it was stronger than ever.

Haoles (non-Hawaiians) dressed in grass skirts and staged bogus luaus in their backyards, sometimes complete with whole roasted

pigs! Bernie, Pat, Al and Clay began performing at backyard luaus in southern California. They weren't paid for these

appearances, but they got all the free food they could eat, and besides, it was good practice for their concert dates. Many

people thought they sounded good enough to record. Eventually, one such person approached them.

"A friend of

ours, that we were going to school with, asked us if we'd be interested in putting songs on a tape," Clay says. "He said,

'maybe when you have children and grandchildren, you can play it for them!' So we did, we put some songs on tape . . . reel-to-reel

tape, that's how long ago this was." Using state-of-the-art stereo recording equipment (rare in the late '50s), the enterprising

friend recorded the as-yet-unnamed group performing ten of their favorite Hawaiian tunes. The playback was fabulous - it sounded

crystal clear, better than anyone had expected. He then dubbed a copy of the tape for the group, but kept the master. Little

did the group know that their recording engineer had ulterior motives. A part-time salesman for a company that sold stereo

equipment, he reckoned that the tape would make an excellent sales tool. Subsequently, when prospective customers came into

the audio store where he worked, they heard the melodic voices of Al, Clay, Bernie and Pat wafting out of a pair of display

speakers. The idea was to demonstrate the clarity of two-channel separation, but one visitor heard something on those speakers

that interested him more.

"A representative

of Hi Fi Records walked in," Clay says. "He was looking for some equipment and heard us (on tape). He asked (the salesman)

who we were." After being told the tale of the tape, the Hi Fi executive expressed interest in meeting the group. One thing

led to another, and the next thing the boys knew, they were sitting in the Hi Fi offices at 7803 Sunset Boulevard, discussing

the terms of a contract. "Recording an album was the furthest thing from my mind," Clay confesses. But recording albums is

generally what happens when you get an album deal, and that's exactly what the group got. In the process, they also acquired

a name: "The daughter of the secretary at Hi Fi Records (said) 'why don't you call yourselves The Surfers?"' The prevailing

image of surfers as blond, freckle-faced teenagers from the Hollywood hills hadn't quite taken hold yet, and historically,

the first people to surf had been native Hawaiians, so . . . why not?

The Hollywood-based

HiFi label was founded in 1956 by Richard Vaughn. An independent label that was among the pioneers of stereophonic recording

on the West Coast, Hi Fi was marketing multi-track singles and albums as early as 1958. Its output was mainly jazz and pop

instrumentals; organist George Wright and Arthur Lyman's Hawaiian quartet emerged as its most commercial artists. Richard

Vaughn headed the company and also handled A & R in its early years. Harold Chang, a member of the Arthur Lyman Group,

spoke about Vaughn several years ago to interviewer Jeff Chenault. "He specialized in hi-fi recordings," Chang explained.

"(Richard) used the best equipment . . . (from) magazines, people heard of his recordings, and when they bought (them), they

became a fan of HiFi Records because of the quality." Vaughn preferred natural acoustics to those found in a recording studio,

so many of his sessions were done on mobile equipment; for sessions, he frequently chose locales not specifically designed

for music recording. Clayton Naluai recalls, "He would go find places where he liked the acoustics, and then he'd set up a

recording studio (there)! He was always walking around, clapping his hands, trying to listen to the acoustics of a room."

Accordingly, The Surfers' first album was recorded in, of all places, the gymnasium of Glendale Junior College!

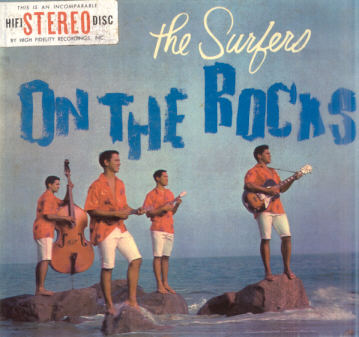

That album was titled

The Surfers On The Rocks. A strictly acoustic affair, with nine of its fourteen selections performed in Hawaiian dialect,

it strikes a heavy folkloric note. This is no Folkways album, though. There's definitely a pop sensibility in the way The

Surfers interpret their lightly swinging repertoire. Cuts like "Nani Wale Na Hula" and "Leahi" seem to radiate sunshine as

they bounce merrily along to Pat Sylva's spirited ukelele rhythm. The humorous "Pidgin English Hula" and the somewhat risqué

"I Got Hooked At A Hukilau" are perfect for the festive atmosphere of a backyard luau. "Papio" and "Tamure, Tamure" are the

first examples of a type of number destined to become a Surfers specialty: The heartily-sung Polynesian chant, peppered with

robust shouts and grunts. The latter song in particular shows off the boys' vocal prowess to fine effect; Alan Naluai soars

overhead while Clay, Bernie and Pat stir up a whirlpool of sound down below. The Surfers’ up tempo material never fails

to entertain, but it's their ballads that tend to leave the strongest impression. The Surfers imbue "Blue Hawaii" with a beautiful

sense of quiet drama. On "Ke Kale Nei Au," their yearning voices ebb and flow at intervals just like an ocean tide. "Leimomi"

is another standout; when honey-voiced Al croons take me back to your island, you can almost hear the fluttering of feminine

heartbeats! Likewise, Clay's bold romanticism on the sailor's lament "I Will Remember You" is so sensual, you can almost feel

the sea spray on your skin. His performance doubtless left any number of women feeling quite . . . moist. In the mid-'60s,

this early stereo album would be reissued under the name Hawaii A Go Go.

Clay

remembers recording that first LP under Richard Vaughn's supervision: "I didn't find it intimidating at all. All we needed

to do was (sing) over and over again until we got it the way we wanted it." Judging by sales, the way they wanted it was the

way the public wanted it, too. On The Rocks became a local best-seller. Modest to a fault, Clay will only allow that

"the album sold a few copies." But forty years after the fact, he still expresses amazement at what happened next. "(Vaughn's

assistant) came back and asked us if we wanted to go into show business! He said if we wanted to . . . he would finance it,

he would give us whatever we needed." The kind of opportunity that most singers chase for years fell into the laps of The

Surfers almost overnight. It was like something out of a dream. "I was out of school and working, and my brother and the other

two guys were still going to school. I was the only one married at that time, and so I told him, 'I've got to think about

it.' " Over a weekend, the boys made the decision that would chart the course of their lives. "Monday morning, I went down

and quit my job, just on the advice of that man," Clay reveals. " I quit my job, and we started. We didn't even have any musical

instruments! We had no idea we'd be doing (music) for the next twenty-six years!"

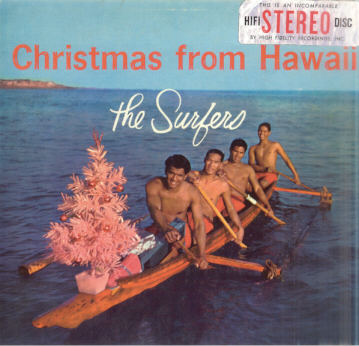

Hi Fi

Records followed up On The Rocks with a superb seasonal album, Christmas From Hawaii with The Surfers. It's

without question one of the most unique Christmas LPs ever recorded. On yuletide swingers like "Here Comes Santa In A Red

Canoe," "Mele Kalikimaka" and "Hawaiian Santa," the boys were accompanied by veteran Hawaiian musicians, including legendary

steel guitarist Jules Ah See and percussionist Harold Chang. Once again, the boys' balladry took center stage; you'd be hard-pressed

to find more beautiful renditions of "Mary's Boy Child," "White Christmas" or "Oh, Holy Night." Christmas chimes, echoing

crisply off a high aluminum ceiling, give the harmonies an ethereal, timeless feel. "We recorded our Christmas album in the

Hawaiian Village Dome," Clay remembers. "We happened to be home at the time, so (Richard Vaughn) recorded it there, but we

recorded most of our albums on the mainland. The pictures of us on the album covers were all taken in California."

Richard Vaughn's

preference for unusual recording locales wasn't the only thing about him that was unconventional. With The Surfers, he also

proved himself capable of innovative marketing strategies. It's long been common knowledge inside the music business that

women are the main consumers of recordings. However, you wouldn't know that from the way most albums were and continue to

be marketed. Images of comely and often scantily clad females have dominated album sleeve art at least since the 1950s; such

images are obviously aimed at a male sensibility. Richard Vaughn bucked this trend. When it was time to photograph The Surfers,

he decided he wanted beefcake, and lots of it! Off to the beach with them, and off with their street clothes. On with tight-fitting

white shorts and Hawaiian shirts open to the waist. He had them photographed in swimwear as they frolicked in the surf, splashed

around in a swimming pool, and cooled themselves under a waterfall. For one photo shoot, he posed them in sarongs. For admirers

of masculine physical culture, it was nothing less than a paradise of Polynesian pectorals!

Shirtless

men in media are nothing unusual today, but in 1958, it was daring. What's more, Clay, Al, Bernie and Pat were Asian-Americans.

Beefcake publicity photos of Asian men are still rarely seen. This ahead-of-its-time marketing campaign turned The Surfers

into sex symbols; they became the visual embodiment of Hawaiian male virility. "We weren't even aware of that," laughs Clay.

"Everything was done by the record company. We didn’t know what was happening . . . we just went along with everything

they said!" But surely they must have suspected something when adoring females began pursuing them with lustful ardor . .

. waiting breathlessly at their dressing room door . . . and making their wives and girlfriends livid with jealousy! Asked

how he and his bandmates dealt with the female attention, gentleman Clayton refuses to kiss and tell. "We dealt with it,"

he chuckles, and leaves the details to our imaginations.

Cutting

albums and posing for photo shoots may have been a thrill, but the boys soon discovered that presenting themselves on stage

was something altogether different. Sent out for a round of personal appearances, they weren't exactly ready for prime time!

The Surfers were an unusual pop vocal group for the '50s in that they accompanied themselves on instruments; this, as Clay

points out, was the norm in Hawaii. Yet they lacked the panache of mainland singing ensembles, and that was also due to Hawaiian

tradition. "Back then in Hawaii," he recalls, "a group of guys sang, or one person sang and didn't say one word. Didn't smile

or anything! Just hanging their heads and singing, and nobody would care." Accordingly, as the boys performed their numbers,

they were stiffer than wooden surfboards! Their very first booking was at The Wagon Wheel Casino in Lake Tahoe, Nevada; Clay

recalls the gig with amusement today, but at the time, it was no laughing matter. "After our first night, they wanted to fire

us!," he says. "Ayre Gross was the owner at that time, and the general manager of the casino was (his) son-in-law." Feeling

that the boys had promise, the casino manager pleaded their case to Gross. "He came up (later) and said we could meet him

in his office the next morning, so we did. He said, 'you guys sing well, but you look like you're scared!' We said, 'we are!'"

The sympathetic manager gave them some rudimentary lessons in stage presentation which they were able to practice for the

next three weeks. It was hardly enough time to perfect a Las Vegas act, but believe it or not, that's where The Surfers were

booked for their second job.

They

were terrified. "On opening night, there was hardly any applause," Clay remembers. "We weren't ready for stage performance!

I thought, what am I doing here?" By the time their show ended, he’d

made up his mind to forget about show business and bolt for home. His heart filled with dread as he met the casino's entertainment

director on the way upstairs to his dressing room. "We met halfway up the stairs, and he looked at me and said, 'Wonderful!

Fantastic! You guys are great! We're gonna keep you around.'" Dumbfounded, Clay staggered to the dressing room and collapsed

in a chair. He couldn't believe what he'd just heard. "We were bad . . . we were lousy!" But even at their worst, The Surfers

seemed destined for a music career. "I thought, Clay, if you're gonna be in this business, you'd better go and learn it."

Determined to create an act that was worthy of a Vegas showroom, young Mr. Naluai gave himself and his group a crash course

in star power and stage presence. Las Vegas was his classroom; Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr, and other '50s legends

were his instructors. "I went from showroom to showroom on my break, on my day off, and watched the different performers perform.

Then I went back, and we did our show." The boys used a tried and true method of self-improvement: learning from older and

more experienced professionals, who in this case were the best entertainers in the world. However, Clayton Naluai prefers

to say it more bluntly: "We copied 'em!" By the time they left Vegas six months later, The Surfers had put together a polished

act that could fill seats and draw big applause. "(Las Vegas) was my training ground," Clay enthuses, "and it was the greatest

training program ever!"

|