|

Having exhausted

his options in Philadelphia, Neil moved to New York City. He also reclaimed his surname around this same time

period. The stage was set for Neil Brian Goldberg to meet and begin working with the man who would arguably become his

strongest musical influence: producer and songwriter extraordinaire Jeff Barry. "I started writing with a guy

named Gil Slavin," Neil explains, "a great piano player (with) a good grasp of what was going on in pop music." Goldberg

and Slavin discovered a sexy, fresh-sounding actress/singer named Susan Morse, and began working with her. (At the time,

she was part of the original Broadway cast of Hair, and she'd later appear in the first Rocky Horror Show.)

They wrote and produced a record for Susan called "Funky Hunk A'Guy" which had that certain magic spark to it.

Right away, they were convinced the song could be a hit. "It was a spin-off of the (Crystals) hit 'He's Sure The Boy

I Love,' the old story of the boy that the world doesn't like, but the girl thinks he's terrific." They had a

great song, and a potentially great artist. All they needed was a recording deal. Neil and Gil shopped the demo

to every publisher and record label they could think of. At Roulette Records, they endured a tense listening session

with the label's intimidating, Mafia-connected CEO, Morris Levy. (Neil opines that, had he desired it, Levy "could easily

have had a part in the Godfather movie!") Doors kept slamming in their faces. From the beginning, though, Gil Slavin

knew who he wanted to place the demo with. "I won't give up on this record," he declared, "until Jeff Barry hears it."

Gil had an "in" with Barry, having helped place a Long Island band known as the Rich Kids (featuring Perry Como's nephew Danny

Belline) on his Steed label. When they entered the Steed Records offices on 52nd Street, Neil was amazed to see

the walls covered with gold records: "Be My Baby." "Chapel Of Love." "Da Doo Ron Ron." Who was this

guy? Only later would he learn of Jeff's amazing track record as a writer/producer, and his long string of hits from

the early '60s. At that moment, Neil just felt an immediate affinity for the lanky, smiling man with sleepy eyes who

was all duded up in western gear. "Jeff and I hit it right off, laughing and throwing around one-liners and song ideas."

Neil played several of his songs, all of which received an enthusiastic reception. Jeff Barry detected a kindred

creative soul; he could definitely hear the light, and see the magical aura Neil's songs gave off. The songwriting styles

of Jeff Barry and Neil Goldberg were remarkably similar, too: Strong hooks, straightforward, conversational lyrics, obvious

country music influence. And magic! "He was blown away," Neil recalls, "because some of my songs and my sense

of humor were so much like his." When he left Barry's office that day, he left with much more than just a deal for "Funky

Hunk'A Guy" (which was later released as an Ampex Records single). Signed to Steed Records as a staff writer along with

Slavin, Neil was also offered "a very strong deal" that included a new chance to record as a solo artist. As his first

job for Jeff Barry Enterprises, a plum project was dropped into his lap ... a project that would expose his songs to millions

of people all over the globe.

Mister Factory

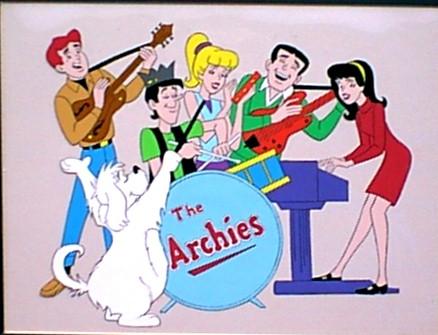

During the

last two years, Jeff Barry had been writing and producing music for the Filmation animated cartoon series The Archie Show.

His soundtrack songs, released on Don Kirshner's custom label, had become big radio hits and made the TV show wildly popular.

Hugely successful was the single "Sugar, Sugar," which broke out of San Francisco in the summer of 1969 for an international

smash. But now, Barry was up to his armpits in work, running his own record label, writing for motion-pictures ( Where

It's At and Hello, Down There had already hit theatres) and juggling numerous side-projects, including two new

cartoon groups ("The Globetrotters," which would come to fruition, and "The Kowboys," which would not). He had no time

to create "Archie" music anymore. Walking in the door and brandishing a songwriting style that mirrored his own, Neil

Goldberg surely must have looked like a Godsend to Barry. As part of his Steed Records deal, Neil agreed to become

the new music director of the studio entity known as The Archies. There was a very important catch, though. For

the third season of the Archie show, there'd be a new "Giant Jukebox" format which demanded twice as much original

music as before. "Each show would play four songs every day," Neil was told. "Thirty-two songs to be written and

produced by me!" It was to be a huge undertaking, and that wasn't the only catch. For contractual reasons, production

credits would still go to Jeff Barry. In addition, his wife's name had to be attached to every song Neil wrote for the

show. "That was how Jeff made any money for the project." Such contracts were neither uncommon nor illegal in

the music business; Barry himself had forgone production credits many times during the early years of his career, and he'd

occasionally been saddled with a bogus co-writer. Still, this was potentially a bitter pill to swallow. If Neil

had any misgivings, though, they were outweighed by the opportunity to hone his writing and production skills in such a high-profile

setting ... not to mention the hefty royalty payments that would result from the "Archie" telecasts!

Writing thirty-two

songs in a couple of weeks is no mean feat. Fortunately, Neil had a backlog of material to draw on, as well as

some new ideas he was eager to execute. He worked fast, and had the ability to multitask. Jeff Barry couldn't

have found a better man to fill his shoes. "There was nothing to it. I knocked off the two-minute-and-thirty-second

ditties one after another while I watched TV or ate a sandwich!" Instead of RCA's Webster Hall Studios where The Archies

usually recorded, Neil booked the sessions at a funky little place called Sound Ideas that he and Gil Slavin were fond of

using. The studio was also popular with jazz musicians. There, he met Hugh McCracken, Ron Frangipane, Joey

Macho and the other Jeff Barry session regulars he would work with off and on for the next few years. "These guys

were cutting hits all over town," Neil says. "It was as if they knew each song before I even played it for them!

We did what were called 'head arrangements' right on the spot, with just my simple chord charts to read from." He appreciated

the professionalism of Barry's crew. "There was never a remark that it was 'just Bubblegum (music).' They played

with all they had ... they put their energy and strength into those tracks, and there was no problem." In other words,

they did it in the name of love, which was exactly the way Neil approached things. Their professionalism contrasted

sharply with the attitude of the Filmation executives who produced the "Archie" show. Neil remembers meeting with

one of them at the beginning of the project. The man proceeded to bob back and forth like a stereotypical seven-year-old

to demonstrate the mentality of the "Archie" target audience. Then he instructed Neil to "write dumb! Don't

try to say anything (relevant).' I told Jeff Barry about the encounter (and) he told me to ignore it ... just follow

my heart and do my best." Neil's heart told him to address issues that he considered important, issues that mattered

to many young people in the early 1970s: World peace, poverty and hunger, the deteriorating natural environment.

He had developed a strong social conscience, and this motivated him to employ his music as a teaching tool. What better

classroom could he find than a national TV network? Jeff Barry had managed to slip a subtle "message song" called "Get

On The Line" into the series the previous year. Neil was determined to push the envelope as far as he could.

"I rewrote the lyrics for (some) of the tracks, which were already cut, but still without the lyrics recorded," he reveals.

"(Then) I wrote (a) few new ones, yet to be cut, with some good messages. It turned out that one out of every three

songs of the Archie's Giant Jukebox project had a good and positive message of some kind."

Now it was

time to record the vocals. Neil returned to Sound Ideas Studio to work with the "voice of Archie," Ron Dante.

He found the experience just as gratifying as working with Jeff Barry's studio musicians, if not more so. "Ronnie Dante

was such a talent," Neil enthuses. "His voice was perfect, and he could sing harmonies at the drop of a hat. First,

I gave him the lyrics and sang him the melody. In about five minutes, Ronnie knew the song, sang the lead perfectly

in one take, and then proceeded to do two or three layers of harmonies on the other tracks." Though Neil supervised

all aspects of the recordings, he allowed Dante some input into the creation of the vocal sound he wanted. They had

lots of fun devising on-the-spot vocal arrangements together. Neil recalls singing background falsetto with Dante on

the song "Little By Little" and a few others, so essentially, for the third season of the "Archie" show, The Archies were

a two-man group. (Toni Wine, Bobby Bloom and Donna Marie, who'd previously sung on Archies singles with Dante and Jeff

Barry were, like Barry, busy with other projects.) They completed recording just in time, because Filmation Studios

was suddenly on the phone, demanding the finished product ahead of schedule. Neil was like a benevolent mad scientist,

cackling maniacally and rubbing his hands together in the background! Well, not really. But that's how he

felt inside. "No one had any idea," he chuckles, "what was about to happen to children's TV, and to the next generation

of kids!" To his delight, the Filmation animators in Hollywood willingly became his collaborators; inspired by Neil's

songs, they crafted a series of groundbreaking cartoon sequences that were psychedelic in appearance and socially-conscious

in attitude. "It seems that when the tracks were rushed out west, a bunch of freaks were doing the animations,"

opines Neil. "They decided to take part in the coup which I had begun!"

It's a bet that

few kids acted like mindless automatons while watching "Archie's Funhouse" during 1970-71. Neil Goldberg's songs were

thought-provoking and dynamic, Ron Dante's lead vocals were incredible, and the cartoon videos for message songs like "One

Big Family," "Love Went 'Round The World," "The Lonely Cricket" and "The Ballad Of 51st Street Park" were no less than riveting.

Nothing like this had ever been seen or heard before on children's television. The most powerful sequence was unquestionably

the one for Neil's environmental plea "Mister Factory." While Dante crooned Mister Factory/Don't you care?/Soon

the children won't have/Any air over a gentle country/rock melody, animated video depicting toddlers in gas masks flashed

on the screen. This powerful image must have scared Filmation executives witless. Probably because of their tight

production schedule, they gave the green light. It became one of the most frequently aired sequences during the

third season. "Of the Archies songs (I wrote), the most important song was 'Mister Factory,'" Neil believes.

"It was the most played, and had a great impact on kids to try to preserve the environment. Also, 'One Big Family' was

a good and important song." Today, he's justifiably proud of the cartoon revolution he touched off, but not so

much at the time. He was afraid that his musician friends wouldn't understand. "I hardly told anyone about

The Archies 'cause I was embarrassed that they were only Bubblegum/"kiddie" songs," he admits, "but now I realize what a major

event each of those shows was." Soon, message songs were popping up in other cartoon shows like "The Bugaloos"

and "Fat Albert and The Cosby Kids." Unfortunately, TV airwaves were the only place people could hear most of these

gems; very few were ever issued commercially. Only four of Neil's compositions ever showed up on an Archies album (fortunately,

"Mister Factory" and "One Big Family" were among them). Contractual restrictions that Neil doesn't completely understand

to this day kept the rest off the commercial market. Yet, he still hopes that all of his revolutionary children's songs

will eventually see the light of day. So do the millions of former Saturday morning TV addicts who've never forgotten

them.

Everybody's Song

No sooner had

Neil completed the Archies project than he was put to work writing for most of the other acts Jeff Barry was producing: Bobby

Bloom, Hank Shifter, The Klowns, The Monkees, One of his tunes, "It's Got To Be Love," appeared on the latter group's

final album, Changes. "The Monkees' session was fun," he remembers. "Micky Dolenz, the lead singer and sort-of

head of the group, was a very friendly guy. Full of wild, almost uncontrolled energy." Neil speaks of a song he

wrote called "A House Above The Sand" that may have been intended for The Monkees, but was abandoned. He wrote alone,

and with collaborators. Most often, it was with Gil Slavin, but a few Goldberg-Renzetti and Bloom-Goldberg numbers also

slipped out. The late Bobby Bloom was one collaborator Neil will never forget. "Bobby had been involved with some

big hits before, one of which was the famous rock classic 'Mony Mony' (by Tommy James and The Shondells), which he sang on

as part of the group. He had been around the business a lot, and many people knew him." People outside the music

business wouldn't know him, though, until they heard his Jeff Barry-produced Caribbean fantasy "Montego Bay." Neil recalls

meeting Bloom right after his single hit the streets in the summer of 1970. "It got some airplay, but after a month

or two, it was not breaking. Bobby Bloom looked so worried. He said to Jeff Barry, 'I think we need another

record.' Jeff put his hand out and said, 'Wait! Give it two more weeks," as if he knew something that Bobby

did not ... he knew hits, and he knew how they happened. Two weeks later, 'Montego Bay' was on (the radio) all over

the country and moving up the charts." Subsequently, Neil co-wrote one of Bobby's best singles, the rousing gospel rocker

"We're All Goin' Home," which charted and was later covered by Hollywood-based a cappella group The Persuasions.

Another Bloom-Goldberg

composition was cut by The Monkees for a 1971 single. However, it became much better known in a cover version by R &

B singer Candi Staton. "'Do It In The Name Of Love' received heavy airplay all over the country! It became #9

on the R & B charts for two weeks in a row." It was probably inevitable that Neil would someday use his personal

philosophy as the title of a song. He recalls how it was created. "We were at Jeff Barry's office in New

York, and I showed Bobby a piece of the song, which I had already written. He liked it, and started playing what I had

on the piano." Neil emphasizes that when Bobby Bloom was in the mood to write a song, "things happened!

He changed the feel, and came up with (a) new rhyme ... and the second line of the chorus ... we then worked on the rest of

the verses together." It would be one of Neil's biggest hits as a writer, though unfortunately, not one of the most

lucrative. "When I counted up the royalties paid to me by BMI for all that airplay," he snarls, "it came to less than

one thousand dollars! It seemed to me that a zero was missing ... I will never have anything good to say about

BMI!" Which explains why he has remained an ASCAP songwriter for most of his career! The last time Neil saw Bobby

Bloom was at the latter's home in Los Angeles, where he moved shortly before his untimely death in a shooting incident.

"He was glad to see me, showed me around the small but totally cool place with steam constantly rising from the swimming pool.

There were colored stage lights that hung from the ceiling, a traffic sign that he had picked up somewhere, lots of cool showbiz

paraphernalia, and a picture of Muhammad Ali, gloves on, ready to punch, at the entrance to (his) one-story Hollywood Canyon

house." Neil remembers that he wasn't Bloom's only guest. Far from it! "A parade of very wealthy and beautiful

women came and went from Bobby's place. I had brought (a girl) over, but the minute she saw Bobby Bloom, I just took

a walk! He had that elegant 'bad boy' thing, which I could not even understand, let alone copy." Yet, Neil harbors

neither jealousy nor hard feelings toward his late friend. "(He was) a true friend, and a real buddy. Bobby never

crossed or deceived me. He just wasn't that kind."

As a Steed

Records staff songwriter, Neil did much writing for (and quite a bit with) Robin McNamara. A lead actor from the Broadway

musical Hair, Robin was the last pop artist broken by Steed. Neil and Robin spent a great deal of time with

each other. "Robin and I took a promo trip up to Canada together," Neil says. "Ou-la-la! Party Tiiiiiiime!

We had some fun, and then we had more fun, and then we really had some fun. Oh, Montreal! The audiences in Canada

loved Robin's performances. He is great on stage, a natural crowd pleaser and exciter." Robin co-wrote his own

Top Ten hit, "Lay A Little Lovin' On Me," and also wrote the bulk of songs for his album of the same title, but Jeff called

in his staff to provide other material. Neil contributed three tunes to the finished product, one of which is

his self-proclaimed favorite of all his compositions from this period. "Now Is The Time" was a Salvation Army-meets-Godspell

number that reflected his growing passion for gospel-tinged message songs. It was, and is, excellent. However,

another of his compositions, the exciting, full-tilt rocker "Got To Believe In Love," garnered the most attention. "I

remember when we cut it at the giant RCA Studios in New York," Neil recalls. Members of the cast of Hair crowded

around the microphone to sing background on the recording. Then something wild happened. "In-between takes, Jeff

Barry took out a small, hard rubber ball, and he threw it 'way up against the forty or fifty foot high walls of the magnificent

studio. The ball careened from one wall to another. It was outrageous!" Neil understood Jeff's impulses;

they were, after all, kindred spirits. "It was just Jeff Barry, having fun. That was what he mostly lived for.

Everything about Jeff's life was for fun, even the making of super hits."

Neil calls

the disc cut that day "a classic Jeff Barry production," and anyone who heard it had to agree. It was chosen as the

follow-up to "Lay A Little Lovin' On Me." It began climbing the charts, but for some reason there wasn't enough airplay,

and it didn't do nearly as well as expected. Yet, Robin McNamara and Neil soon formed a writing team in order to generate

new singles. They were creatively compatible, and soon hit upon a commercial style. "We would just be hanging

out, laughing, swapping funny stories," Neil says, "and then one of us would say something, and we would be into a song."

Robin's personal favorite of their collaborations was a heartfelt ballad that turned on the theme of world peace. Neil

loved the song, too. "When we wrote 'Rise and Shine,' it was just a spontaneous song," he remembers. "I just started

playing guitar, and we both started singing lines. Line after line, the song was waiting to be born." The subsequent

Jeff Barry production rides high on soaring harmonies and surging strings. "Robin and I both felt that it was a gift

to the world from somewhere beyond," Neil states, and, musical sorcerer that he is, he should know! "It was a time of

tension between people and nations, (and) we wanted to write something that would matter." Another Goldberg-McNamara

composition (with contributions from Jeff Barry) had a decidedly more earthy flavor to it: The naughty number known as "Mary,

Janey And Me." It was Robin's last Steed single, based on his own rather, ahem, adventurous love life. "As I recall,

Robin and I were in (Jeff's office) alone, just hangin' out, and then Jeff came in." Before long, the mood and the conversation

turned decidedly ribald. "Robin started telling his story as Jeff and I wisecracked, and then we all started throwing

lines around ... within a short time, there was (this) cute, bawdy little song!" Barry cut it with an irresistible quasi-reggae

arrangement and called in The Archies' Toni Wine for prominent backing vocals. Holding forth with some very provocative

verses (I wanted to take 'em both home/And I told 'em what I wanted to do/They said "It's all right with us, boy/If it's all

right with you"), "Mary, Janey And Me" was probably the first pop song about an explicit one-man-with-two-women menage a trois.

It never charted, which isn't surprising; pop radio in 1971 wasn't ready for such racy subject matter. However, its

reputation has spread far and wide, and when the single comes up for auction on eBay, money can almost buy it. In 2005,

Robin McNamara and Jeff Barry re-invigorated this incendiary ditty by cutting it as a straight-ahead reggae recording.

We probably haven't seen the last of Goldberg and McNamara working as a team, either. Neil confirms that "we have been

in touch, and plan to write again together in the near future."

|